Tasmanian Native Hen: Remarkable Flightless Bird of Tasmania

Tasmanian Native Hen, a bird that is both unique and highly adaptable. What makes it so interesting? Well, it’s a flightless rail that managed to thrive in an environment where most of its kind would vanish. This bird is a homebody too—you’ll find it all across Tasmania, mostly in farmland, river flats, and marshes. And here’s a fun fact: despite being a rail, it can sprint at nearly 50 kilometers per hour using its wings like stabilizers. That’s faster than many pheasants can run.

Tasmanian Native Hen Taxonomy / Classification

- Common Name: Tasmanian Native Hen (also spelled Native‑hen or Nativehen)

- Scientific Name: Tribonyx mortierii

- Family: Rallidae (rails, coots, moorhens)

- Order: Gruiformes

- Class: Aves

Also read: /the-snowy-owl/

It belongs to the rail family—ground birds that usually scurry more than they fly. But the Native Hen is a standout for opting out of flying altogether.

Tasmanian Native Hen Physical Description

This bird is stocky and robust, measuring 43–51 cm long. Its upper body is olive-brown, with a white patch on the flank. Underneath, it shifts to a bluish-grey—darker and subtly tinted. It carries a short, upright tail, almost black in color.

The bird has strong, gray, scaly legs with sharp claws at the ends. Those legs are made for running, not flying. Its eyes are bright red, and the bill features a greenish-yellow frontal shield.

Juveniles look like paler versions of adults, with spotted underparts, but the same striking red eyes and yellowish bill. Males tend to have slightly longer bills and legs, but it’s hard to tell genders apart by sight.

Habitat and Range of Tasmanian Native Hen

You’ll only find the Tasmanian Native Hen in its native habitat of Tasmania. It thrives in various parts of the state, such as marshes, river flats, pastures, and grassy areas near water, but steers clear of the western and southwestern wilderness regions.

Interestingly, a population introduced to Maria Island is doing well, and the species once lived on the Australian mainland until about 4,700 years ago, likely driven away by dingoes or changing climate.

Diet and Feeding Habits of Tasmanian Native Hen

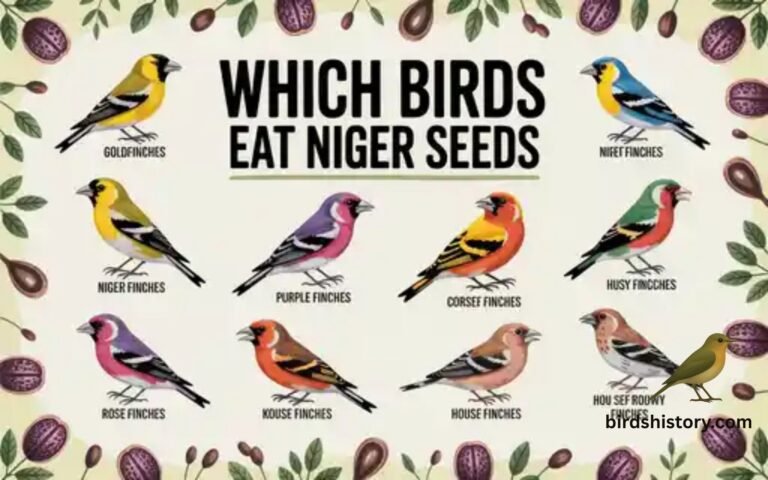

Native Hens are mainly grazers. They forage on grass shoots, low herbs, seeds, and vegetation during daylight. Young birds also snack on insects and occasionally fruit from orchards.

They’re considered secondary grazers, meaning they rely on other species or disturbances (like grazing animals or controlled burns) to keep grass at the right length for feeding. Farming and rabbit grazing have unintentionally created ideal feeding grounds for them.

Tasmanian Native Hen Behavior and Lifestyle

These hens are social and territorial. They typically live in groups of 2–5 birds, with offspring from the prior breeding season staying to help with the next brood. Territories can be up to 5 acres, defended with aggressive calls and displays. Fights happen—complete with pecking, kicking, and even drawing blood.

They can’t fly, but boy can they run—recorded speeds reach 48 km/h (30 mph), using wings to stay balanced.

Their vocal repertoire is diverse, with 14 different calls, including low grunts, alarms, and a see-sawing duet that ends in a screech—often performed in unison. They even call at night.

Tasmanian Native Hen Reproduction and Lifespan

Native Hens breed once a year, usually between July and December—later in wetter or food-rich years. If circumstances are favorable, they may raise a second set of offspring.

Behaviors around breeding are unique. Some groups are monogamous, but many are polyandrous—one female mates with multiple males in her group. And juvenile birds often stay behind to help raise the new chicks.

Nests are simple—flattened grass mats nestled in tall grasses near water. A typical clutch consists of 5 to 8 eggs, each measuring around 56 x 38 mm and featuring a dull yellow or buff color with spots of reddish-brown and lavender. Groups even build secondary “nursery nests” for chicks to sleep or hide in.

Chicks hatch covered in fluffy, dark brown down. Parents care for them over several weeks, teaching them to feed and stay safe. Exact lifespan figures are scarce, but as a stable species, it’s likely they live several years in the wild.

Predators and Threats to Tasmanian Native Hen

Native Hens face threats from natural predators and environmental pressures. Predators such as Tasmanian devils, quolls, ravens, marsh harriers, and eagles take eggs and adults occasionally.

Still, they remain relatively common thanks to abundant habitat and their social resilience.

Conservation Status of Tasmanian Native Hen

The IUCN lists the Tasmanian Native Hen as Least Concern—populations are stable and widespread. Since 2007, it has been legally protected under Tasmanian legislation.

However, the possible introduction of red foxes remains the biggest future threat—they could rapidly harm native populations. Its current protected status helps guard against that.

Interesting Facts About Tasmanian Native Hen

- Nicknames like turbo chook, narkie, or waterhen reflect the bird’s quick pace and local folklore .

- It once inhabited mainland Australia but declined with the arrival of dingoes around 4,700 years ago.

- Their social dynamics—polyandry and group-based chick-rearing—are rare in the bird world .

- Running speed up to 48 km/h makes them one of the fastest ground rails around.

Conclusion / Summary

The Tasmanian Native Hen is a grounded marvel—flightless but fast, social yet fiercely territorial, and deeply tied to open grasslands near water in Tasmania. It’s a bird that adapted to changes, survived human arrival, and now stands as a symbol of resilience.

Learning about its behaviors, habitat, and how it’s protected teaches us the value of adaptability and the importance of conservation—even for species that seem to be doing well. They remind us that every bird, no matter how common, has a story worth sharing and preserving.

FAQs About Tasmanian Native Hen

Where is the Tasmanian Native Hen found?

Only across Tasmania, especially in grassy areas near water.

Can Tasmanian Native Hen fly?

No, it’s a flightless rail but can run very fast.

What does Tasmanian Native Hen eat?

Mainly grass shoots, herbs, seeds, and occasionally insects and fruit.

When does Tasmanian Native Hen breed?

Between July and December, sometimes twice a year if food is plentiful.

How many eggs does Tasmanian Native Hen lay?

Typically 5 to 8 per clutch.

What is Tasmanian Native Hen IUCN status?

Listed as Least Concern.

What predators does Tasmanian Native Hen face?

Tasmanian devils, quolls, ravens, marsh harriers, and eagles.

Is Tasmanian Native Hen protected?

Yes—legally protected in Tasmania since 2007.

Why is Tasmanian Native Hen called a ‘turbo chook’?

Because it can run fast and is often seen in open areas.

What makes Tasmanian Native Hen’s social structure unusual?

Groups often share one breeding female who mates with multiple males, and young help raise new chicks.