Pallas’s Cormorant: The Spectacled Giant Lost to Time

Pallas’s Cormorant bird almost twice the size of most cormorants, living on remote rocky coasts, reluctant to fly yet dominating the seas around the Bering Islands. Meet Pallas’s Cormorant, also known as the Spectacled Cormorant (scientific name Urile perspicillatus). This bird is fascinating for many reasons: it was once the largest known cormorant, it had unusual traits that hinted at semi-flightlessness, and it vanished relatively recently, in human terms. Its story raises questions about extinction, human impact, and what we lose when a species disappears.

Pallas’s Cormorant lived in the far northeast of Russia — Bering Island, possibly parts of Kamchatka and nearby coastal areas. It was described first in the 18th century, and by the mid-19th century it was gone. One surprising fact: fossil remains show that its prehistoric range may have extended as far as Japan around 120,000 years ago.

Taxonomy / Classification of Pallas’s Cormorant

Here’s how Pallas’s Cormorant fits into the tree of life:

- Common Name: Pallas’s Cormorant (also Spectacled Cormorant)

- Scientific Name: Urile perspicillatus (synonym Phalacrocorax perspicillatus)

- Family: Phalacrocoracidae (the cormorant family)

- Order: Suliformes

- Class: Aves

Also read: /california-condor/

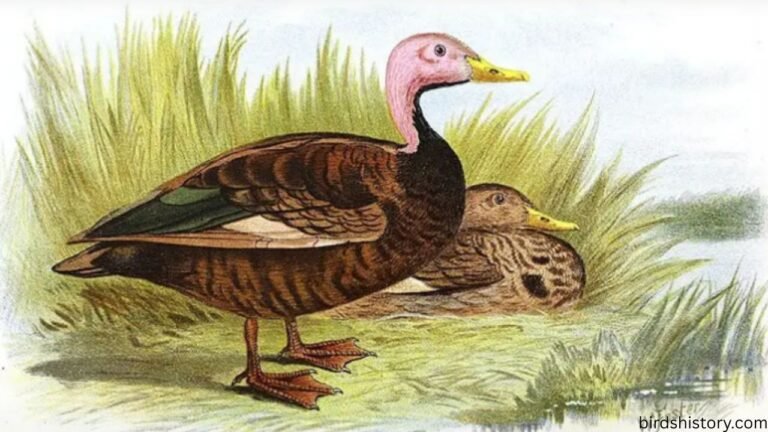

Physical Description of Pallas’s Cormorant

Pallas’s Cormorant was remarkable in its appearance and size.

- Size & build: It was the largest cormorant known. Length estimates go up to about 100 centimeters (≈ 39 inches), with body mass estimated between 3.5 to 6.8 kilograms.

- Plumage & coloration: Mostly glossy black with a lustrous sheen — a green gloss in parts, purple on wings in some specimens. There was a large white patch on its lower flanks, just above the legs.

- Head, beak, bare parts: It had small patches of bare skin around the face and eyes. In breeding condition these bare areas might have changed color (dull yellowish or orangey-reddish). It also had hair-like pale yellow feathers on the head and upper neck, and a prominent crest in males during the breeding season. Females lacked the crest.

- Flight adaptations: Its sternum and wing bones suggest reduced power of flight. Whether it was fully flightless is debated; most evidence suggests it was at least reluctant to fly, possibly making only weak or short flights.

Habitat and Range

- Geographic range: Earlier limited to Bering Island (Commander Islands, Russia), possibly nearby islets and the coast of Kamchatka. Fossil evidence extended its prehistoric range to parts of Japan around 120,000 years ago.

- Preferred environment: Coastal marine environments, rocky shores, islets and offshore islands. It nested by the sea, likely feeding in nearby marine waters.

- Migration: There is no evidence of long-distance migration. It was a resident bird in its range until its extinction. Its relatively large size and perhaps reluctance to fly likely limited its capacity for long migrations.

Pallas’s Cormorant Diet and Feeding Habits

- What it ate: Fish were its primary food source. Like other cormorants, it was a diving predator.

- How it caught food: Probably diving from the water’s surface, using its beak to grasp fish. Because of its likely strong body and aquatic adaptations, it may have been efficient under water. However, since detailed observations are sparse (it had already become rare as scientists observed it), much of this is inferred from related species.

- Interesting feeding behavior: Nothing much is known in the way of specialized behavior like cooperative fishing or special tools. But its size, and adaptations, possibly allowed it to exploit fish or marine life not available to smaller cormorants.

Behavior and Lifestyle

- Social vs solitary: Likely somewhat social during breeding, as coastal seabirds often nest in colonies, though records are limited. Observations from Steller (in the 1740s) describe them in numbers.

- Flight style: Weak flyer or reluctant flier. Likely strong in water rather than in the air. Wing and sternum morphology suggest some reduction in flight muscles.

- Nesting habits: Probably nested on rocky cliffs or shores. Exact nest structure is not well documented.

- Vocalizations / calls: There is very little reliable information about voice or call. Because the species was extinct early after scientific observation began, and few people recorded or described its calls.

- Mating rituals: Limited documentation. Presence of crest and bright bare parts in males during breeding seasons suggest some display behavior. The sexual dimorphism (crest in males, none in females) hints display for attracting mates.

Pallas’s Cormorant Reproduction and Lifespan

- Breeding season: Information is scarce. But breeding likely occurred during the warmer months in the region (summer) when marine productivity and daylight are favorable.

- Nests / eggs: Number of eggs, coloration, incubation time — these are undocumented in the scientific record. The species had almost disappeared before many detailed naturalist observations of such traits.

- Lifespan: No precise data. Considering its size and that large seabirds tend to live several years, possibly multiple decades. But because it is extinct and was poorly observed, any number would be speculative.

Predators and Threats

- Natural predators: Seabirds generally face predation on eggs or chicks from gulls, foxes (especially on islands), or other opportunistic predators. On Bering Island, Arctic foxes and possibly other mammals may have had access to nests.

- Environmental threats: Before modern conservation science, threats like habitat disturbance by humans, hunting, collection, and possibly introduced predators would have posed serious risks.

- Human impact:

- Hunting for food and feathers was a major factor in its decline. Early Russian explorers, fur traders, and settlers exploited many island species.

- Collection of specimens for natural history collections.

- Possibly disturbance of breeding colonies.

Pallas’s Cormorant Conservation Status

- Is it endangered or extinct? Pallas’s Cormorant is extinct. The extinction date is often placed around the mid-1800s, often cited as around 1850. Some last reliable observations were around 1852.

- IUCN status: Listed as Extinct.

- Conservation efforts: Because its extinction preceded modern conservation frameworks, there were no systematic conservation efforts to save Pallas’s Cormorant. What remains are specimen collections, fossil records, and historical writings. Recent studies (such as reviewing museum specimens and fossil finds) are helping us understand its life history.

Interesting Facts About Pallas’s Cormorant

- Largest cormorant ever known: Its size makes it stand out; larger than any modern cormorant species.

- Reduced flight capacity: It appears to have been reluctant to fly, with skeletal features that suggest reduced flight ability. That makes it behaviorally similar in some ways to the Flightless Cormorant (found in the Galapagos), though not fully flightless.

- Prehistoric range extension: Fossils dated ~120,000 years old have been found in Japan, showing that its range was wider in the past.

- Taste and use by indigenous people: Historical records say that the bird was eaten, and that its flesh was considered good by some. Also hunted for feathers.

- Very limited specimens: Only six skins are known in museums around the world. Osteological (bone) materials have been collected too, but the overall sample is small.

- Names and symbolism: Named Pallas’s Cormorant by Peter Simon Pallas; the common name “spectacled” refers to the bare skin patch around the eyes that looked like spectacles in some descriptions.

Conclusion / Summary

Pallas’s Cormorant is a poignant example of what a species lost to human impact can teach us. Once the largest known cormorant, with a range in the chilly seas around the Bering Islands and possibly beyond, it had adaptations hinting at a semi-flightless, marine-oriented life. It faded into extinction by the mid-19th century, largely because of hunting, collection, and habitat isolation.

Learning about this bird helps us reflect on how fragile certain species are, especially those with limited ranges, large size, or specialized habits. Documenting and preserving what remains — fossils, specimens, historical accounts — gives us a clearer picture of the natural world we once had and underscores the importance of protecting what remains.

FAQs About Pallas’s Cormorant

Here are some questions people often ask about Pallas’s Cormorant:

- Q: When did Pallas’s Cormorant go extinct?

A: Around the mid-1800s, with last reliable observations about 1852. - Q: Where was Pallas’s Cormorant found?

A: Mainly on Bering Island in the Commander Islands, possibly other nearby islands and coastal Kamchatka. Also prehistoric fossils in Japan suggest a wider ancient range. - Q: How large was Pallas’s Cormorant?

A: Up to about 100 cm (39 in) long, with weight estimates between roughly 3.5 and 6.8 kg. - Q: Could Pallas’s Cormorant fly?

A: It seems to have had weakened flight abilities — reluctant to fly and possibly only capable of limited flight — but not fully flightless by all accounts. - Q: What did Pallas’s Cormorant eat?

A: Fish, caught by diving in marine coastal waters, similar to other seabirds in its family. - Q: Why is Pallas’s Cormorant called “spectacled”?

A: Because it had bare eye/surround patches that appeared like spectacles in some descriptions, especially combined with pale yellow facial feathers. - Q: Are there any specimens left?

A: Yes — there are six skins in museums globally, plus osteological remains (bones, fossils) in various institutions. - Q: What caused Pallas’s Cormorant extinction?

A: Main causes were human: hunting for food and feathers, collection by naturalists, possibly disturbance of habitat, and introduction of predators or human influences. - Q: Is Pallas’s Cormorant unique among cormorants?

A: Yes. Its sheer size, reduced flight adaptations, and relatively recent extinction make it stand out. Also its prehistoric range shows it once had a larger distribution. - Q: What lessons do scientists draw from its story?

A: That species with limited geographic ranges are vulnerable, that human exploitation can cause extinction even when population seems stable, and that preserving specimens, fossils, and historical data matters for understanding what was lost and for guiding conservation.