Huia New Zealand Lost Jewel & Lessons from Its Silence

Huia New Zealand was more than just a bird. It stood for something sacred, a symbol of artistry, status, and the deep connection between people and place in New Zealand. Native to the North Island, the huia vanished by the early 20th century—yet its story still captures imaginations. One surprising fact: male and female huias looked so different that early scientists thought they were two separate species.

Huia Taxonomy / Classification

- Common Name: Huia

- Scientific Name: Heteralocha acutirostris

- Family: Callaeidae (New Zealand wattlebirds)

- Order: Passeriformes

- Class: Aves

Also read: /bali-starling/

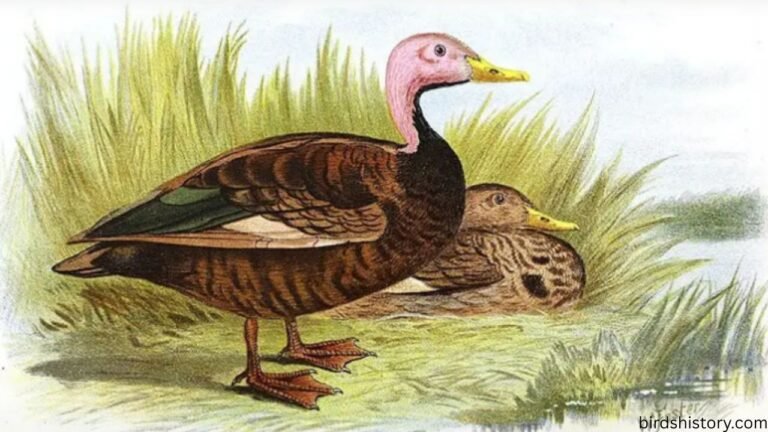

Huia Physical Description

- The Huia was a fairly large songbird, about 45–48 cm (18–19 inches) long, with the female slightly larger than the male.

- Its plumage was glossy black with a greenish or bluish iridescent sheen, especially on the upper parts and around the head.

- Tail feathers had a distinctive white band at the tips, making the tail stand out in flight or even when stationary.

- One of its most remarkable features was the huge difference in bill shape between males and females. The male’s bill was stout, straight or only slightly curved, strong—good for chiseling or levering at wood. The female’s bill was longer and very curved downward—used to probe into places the male’s bill could not reach. This sexual dimorphism in bill form is among the most extreme recorded in birds.

- At the base of the bill on both sides there were fleshy wattles—bright orange—characteristic of the wattlebird family. These were ornamental and part of what made the huia so beautiful. Legs were bluish-grey. Juveniles had less pronounced wattles and less sheen.

Habitat and Range Of Huia

- The Huia was endemic to the North Island of New Zealand. Before human settlement it was more widespread; later it became confined to certain mountain ranges: the Ruahine, Tararua, Rimutaka, and Kaimanawa ranges, and around Wellington in the southeast.

- Preferred habitats were native forests, both lowland and montane, with plenty of mature, old trees, especially rotting wood and decaying logs. These provided food (insects, larvae) and nesting sites.

- It is believed huia moved seasonally—higher elevations in summer, lower elevations in winter—following food availability and forest conditions.

Must Read About: /guam-kingfisher-history/

Diet and Feeding Habits Of Huia

- The huia was omnivorous with a strong leaning toward invertebrates. It ate insects, larvae (especially beetle larvae, such as huhu beetle), spiders, and possibly fruit or soft berries from native plants.

- Thanks to the very different bills of males and females, they could exploit slightly different feeding niches. The male’s stronger, stouter bill was suited to prying bark or rotting wood to expose hidden larvae. The female’s long curved bill could probe deeper into cracks or under bark where the male could not reach. This reduced competition between the sexes.

- Foraging behaviour included moving among layers of forest vegetation, hopping, bounding rather than long sustained flights, inspecting dead wood, fallen branches, bark, and leaf litter. Roaming in pairs or possibly small groups.

Behavior and Lifestyle

- The huia was not a bird of long migration. It was resident in its range and moved locally in elevation or habitat as conditions changed.

- It was relatively social in terms of pair bonds; males and females paired together, often found feeding together. They maintained territories in suitable forest patches.

- They were not strong flyers in the sense of long-distance flight. Instead they used bounding flights—short hops, glides between branches, low flight under forest canopy.

- Vocalizations: they had various calls—musical whistles, flute-like tones, calls audible up to some distance. Also distress calls. The Maori name “huia” may be linked to the bird’s cry.

Huia Reproduction and Lifespan

- Breeding details are not well known in full. Pairs would raise about two to three chicks per year in ideal conditions. The nest would be in tree cavities or hollow parts of trees. The nest was built with forest materials.

- Egg colour, exact incubation period, nestling duration are less well documented. Because the huia became rare before detailed studies could be made, many aspects of its reproductive biology remain partly speculative.

- Lifespan is also poorly documented. As with many forest songbirds, lifespan may have been several years—perhaps 5-10 years in the wild—but nothing certain since no long-term monitoring was possible before extinction.

Predators and Threats

- Natural predators: before human arrival, some native predators (birds of prey) might have preyed upon eggs or young. Also, forest changes, storms would affect nests. But most serious threats came from introduced predators: rats (kiore), possums, stoats, cats etc once these animals were introduced.

- Habitat loss: widespread logging, burning, clearing of native forest for farming and settlement dramatically reduced habitat. Old growth trees, rotting wood, hollows—all of which huia depended on—were lost.

- Hunting and collection: The huia was hunted for its feathers and skins—especially its tail feathers, which were prized by Māori and later by European collectors. Specimens were collected for display. Hunting pressure increased with European arrival.

Huia Conservation Status

- The huia is officially Extinct (IUCN status EX).

- The last confirmed sighting was 28 December 1907 near the Tararua Range in the southern part of the North Island.

- There were many unverified sightings through the early decades of the 20th century, but none confirmed.

- Some legal protection was enacted: the Wild Birds Protection Act was amended in 1892 to try to protect the huia. However enforcement was weak and came too late.

Interesting Facts About Huia

- The extreme bill sexual dimorphism of the huia is often cited in textbooks as a classic example of how males and females can evolve very different tools for feeding, reducing competition.

- Huia feathers are culturally sacred to Māori. Wearing huia feathers (especially tail feathers) was reserved for chiefs and people of high rank. The bird was considered tapu.

- A single huia tail feather recently sold at auction for a world-record price, illustrating how its beauty and rarity continue to capture public fascination.

- The huia was voted “Bird of the Century” in certain New Zealand conservation polls, even though it no longer lives. This reflects how deeply it is embedded in national identity.

Conclusion / Summary

The huia was a bird of striking beauty and striking difference between males and females. It lived in native forests of New Zealand’s North Island, dependent on rotting wood, old trees, complex forest structure, and specific ecological balance. Its large, curved female bill and shorter male bill were adapted to different feeding methods that reduced competition. It was seen as sacred by Māori, deeply embedded in cultural life.

The huia’s extinction resulted from a combination of human impacts: forest destruction, introduced predators, overhunting for feathers and specimens. Laws to protect it came too late or were not strongly enforced. The last confirmed sighting was in 1907, though stories and unverified sightings lingered.

Why its story matters:

- It reminds us of the link between culture, ecology, and identity. The loss of the huia is not just ecological; it is cultural.

- It shows how specialized ecological adaptations (like its bill shape, dependence on old trees) make species vulnerable when environments change.

- It demonstrates that legal protection, while necessary, must be timely and enforced.

- It has lessons for conserving other endangered species before they slip into extinction.

Even though the huia is gone, its feathers, its story, and its symbolism remain alive. It continues to inspire conservation, to remind us of what is lost, and of what we must protect now.

FAQs About Huia

Why did the huia go extinct?

The huia’s extinction resulted from loss of its forest habitat, introduced predators, and hunting for feathers and specimens. These combined pressures overwhelmed the species.

When was the last confirmed Huia sighting?

The last confirmed observation was 28 December 1907 in the Tararua Range.

Did people try to protect the huia?

Yes. Laws like the 1892 amendment to the Wild Birds Protection Act were passed. But the protections were weak, too late, or poorly enforced.

How did male and female huia differ?

Males had strong, shorter bills suited to chiseling wood. Females had long, curved bills to probe deep crevices. This difference is among the most extreme sexual bill dimorphisms in birds.

What did the huia eat?

Mostly insects and insect larvae (beetles especially), spiders, some fruit. Males and females used different feeding techniques thanks to their different bill shapes.

Where was the huia found?

In the North Island of New Zealand. Before European colonization it was more widespread. Later its range was restricted to certain mountain ranges and forests.

Was the huia a good flyer?

No. It was not built for long flights. It moved through forests using bounding flight, hopping from branch to branch, rather than long sustained flights.

What role did huia play in Māori culture?

Huge. Feathers from huia tail and wattles were used as symbols of status. Only high chiefs wore them. The bird was considered sacred (tapu). Its feathers were used in ceremonial adornments.

Are there any preserved huia specimens?

Yes, many museum specimens exist around New Zealand and overseas. Feathers, skins, stuffed birds, etc. These help researchers understand the bird’s morphology and biology.

What can we learn from the huia’s extinction?

We learn that a species with specialized feeding, habitat needs, cultural importance, and low tolerance of environmental change can be lost quickly. Also, conservation actions must be timely, backed by enforcement, and should prevent habitat loss and invasive species before it’s too late.