The Mighty Moa History – Giants of New Zealand’s Past

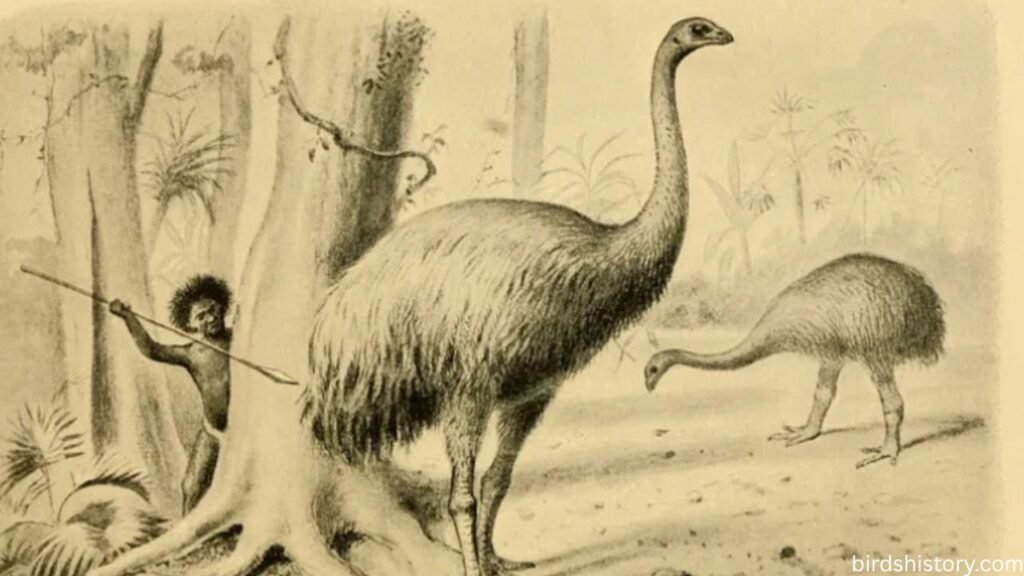

The Moa was one of the most extraordinary birds to ever walk the earth. Native to New Zealand, this group of giant, flightless birds once dominated the islands’ forests, grasslands, and shrublands. Some species stood over 12 feet tall, making them the tallest birds that ever lived.

What makes the Moa so fascinating is not only its size but also its unique place in ecology and human history. Before people arrived in New Zealand, the Moa had no mammalian predators. Instead, their main threat came from the Haast’s eagle, the largest eagle in the world. Within just a few centuries of human settlement, however, the Moa was driven to extinction by hunting and habitat destruction.

One surprising fact: the Moa family included several species ranging from turkey-sized birds to colossal giants taller than an adult human. They were a diverse group that filled many ecological niches across New Zealand.

Moa Taxonomy / Classification

- Common Name: Moa

- Scientific Name: Dinornithiformes (an order containing multiple species)

- Family: Various families within Dinornithiformes, including Dinornithidae and Emeidae

- Order: Dinornithiformes

- Class: Aves

Also read: /wandering/

The Moa belonged to the ratite group of birds, which also includes ostriches, emus, cassowaries, kiwis, and rheas. Unlike many other ratites, Moa completely lacked wings, not even tiny vestigial ones.

Moa Physical Description

Moa were highly variable in size depending on the species.

- Height: Ranged from 3 feet (smaller species) to over 12 feet (giant moa).

- Weight: From 30 pounds to nearly 600 pounds.

- Plumage: Likely brown to gray feathers, with a soft, shaggy appearance for camouflage. Some species may have had speckled or striped patterns.

- Beak: Varied depending on diet—some were sharp and hooked for browsing tough shrubs, others broad for grazing.

- Legs: Strong and robust, adapted for walking long distances.

- Wings: Completely absent—unlike ostriches or kiwis, moa had no wing bones at all.

Sexual Dimorphism: In some species, females were almost twice the size of males. This is one of the most extreme examples of sexual size difference in birds.

Unique Trait: The lack of wings made moa unique among flightless birds, showing how fully adapted they were to a ground-dwelling lifestyle.

Habitat and Range Of Moa

Moa were found only in New Zealand, where they occupied a wide range of environments.

- Range: Both the North and South Islands of New Zealand.

- Habitats:

- Forests (for browsing species)

- Grasslands and shrublands (for grazing species)

- Alpine zones (for hardy, smaller species)

- Migration: Moa did not migrate long distances but may have moved seasonally between forest and open areas in search of food.

Their diversity meant that nearly every habitat in New Zealand had at least one species of moa playing a key ecological role.

Moa Diet and Feeding Habits

Moa were herbivores, and different species specialized in different diets.

- Grazing Species: Ate grasses, herbs, and low vegetation.

- Browsing Species: Fed on leaves, twigs, seeds, and fruits from shrubs and trees.

- Beak Adaptations: Sharp, hooked beaks for browsing tough plants; broad beaks for grazing.

- Digestive System: Like many herbivorous birds, moa likely swallowed stones (gastroliths) to grind up plant material in their gizzards.

Fossilized droppings (coprolites) have revealed details of their diet, showing a variety of plant species consumed. Moa were critical for seed dispersal and maintaining plant diversity in New Zealand ecosystems.

Behavior and Lifestyle

Moa behavior can only be inferred from fossils and comparisons with other ratites, but scientists have pieced together a reasonable picture.

- Social Structure: Some species likely lived in groups, while others may have been solitary.

- Movement: Moa were strong walkers but not particularly fast runners, relying on size and camouflage for protection.

- Nesting: Nests were simple ground scrapes, often in sheltered areas.

- Vocalizations: Unknown, but may have included deep booming calls or grunts, similar to emus or cassowaries.

- Daily Life: Likely spent much of their time foraging, with large-bodied species requiring vast amounts of vegetation.

Their calm, slow lifestyle made them vulnerable once humans arrived with hunting tools and dogs.

Moa Reproduction and Lifespan

Moa reproductive strategies were similar to those of other large, flightless birds.

- Breeding Season: Likely spring and summer.

- Nests: Shallow depressions in the ground, lined with vegetation.

- Eggs: Very large, some over 9 inches long. Eggshells have been found in archaeological sites.

- Clutch Size: Likely 1–2 eggs per season.

- Parental Care: Male moa may have incubated eggs, as seen in other ratites.

- Lifespan: Estimated at 40–50 years for larger species.

The small clutch size and long lifespan meant moa populations recovered slowly from hunting, making them highly vulnerable to overexploitation.

Predators and Threats

Natural Predators

- Haast’s Eagle: The largest eagle ever known, with a wingspan up to 10 feet, preyed primarily on moa.

- Other Predators: None—before humans, moa faced few land-based threats.

Human Impact

- Hunting: Māori settlers arrived around the 13th century and quickly began hunting moa for food, feathers, and bones.

- Habitat Destruction: Early burning of forests reduced suitable habitat.

- Egg Collection: Human harvesting of eggs reduced reproduction rates.

Within just 200 years of human arrival, moa populations collapsed completely. By the early 15th century, they were gone.

Moa Conservation Status

- IUCN Status: Extinct.

- Extinction Timeline:

- Arrival of Māori in New Zealand: around 1250–1300 CE.

- Rapid hunting and habitat destruction.

- Extinction by ~1400 CE.

Unlike later extinctions, moa disappeared before Europeans arrived, meaning their loss was entirely due to Polynesian settlement.

Today, moa are often discussed in the context of de-extinction projects, as scientists explore the possibility of using DNA from well-preserved fossils to recreate them.

Interesting Facts About the Moa

- Moa were the only birds completely wingless, with no wing bones at all.

- The Haast’s eagle evolved to hunt moa, becoming the largest eagle in history.

- Some moa species were taller than any other bird, standing over 12 feet high when stretching their necks.

- Moa bones and eggshells are still found in New Zealand caves and swamps.

- Māori used moa bones to make fish hooks, tools, and ornaments.

- The word “moa” comes from the Polynesian word for chicken.

- Moa are sometimes called the giant cousins of kiwis, as both are ratites native to New Zealand.

- Moa DNA studies have helped scientists understand ratite evolution worldwide.

Conclusion

The Moa was a true giant of the bird world—diverse, unique, and perfectly adapted to the landscapes of New Zealand. From turkey-sized grazers to towering giants, moa species filled vital ecological roles for centuries. But their size, slow reproduction, and lack of natural defenses left them vulnerable. Within just two centuries of human arrival, they were gone forever.

The extinction of the moa is one of the clearest examples of how quickly human activity can erase even dominant species. Today, their story serves as both a scientific fascination and a conservation warning. As we face biodiversity crises around the world, the moa reminds us that abundance is not a guarantee of survival.

Though extinct, the moa lives on in cultural stories, scientific studies, and the imagination of people worldwide. It remains a symbol of New Zealand’s natural heritage and a lesson in the fragility of life.

FAQs About Moa

1. What was the Moa?

A group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand.

2. What was its scientific name?

They belonged to the order Dinornithiformes.

3. How tall was the Moa?

Some species stood over 12 feet tall, making them the tallest birds ever.

4. Could the Moa fly?

No, they were completely wingless and could not fly.

5. What did the Moa eat?

They were herbivores, feeding on grasses, leaves, seeds, and fruits.

6. Who hunted the Moa?

The Māori people hunted them for food, feathers, and bones.

7. When did the Moa go extinct?

By around 1400 CE, just 200 years after human settlement.

8. Did the Moa have predators?

Yes, the Haast’s eagle was their main natural predator.

9. Are scientists trying to bring the Moa back?

Some DNA research has explored the idea of de-extinction, though it’s still theoretical.

10. Why is the Moa important today?

It symbolizes the impact humans can have on ecosystems and the importance of conservation.